Bringing out our dead

Unless a demented co-pilot plunges his Airbus into the French alps with the loss of all on board, or Jihadists decapitate or burn alive their captives, we seldom reflect on news reports of horrific death. For most people, if they see a body at all, it is of a dog run over by a car or a crash victim on the side of the road covered with a blanket. Or it’s at a funeral in the religions that keep the casket open for viewing by mourners filing past…

Northern News, October 1993

MOGADISHI FROM THE AIR

Danger and destruction have a prominent place in the turbulent past. In six of the twelve countries I have worked in over the past two decades I have reported on nine wars – some places a have had two wars in that time, counting among the nine – and I covered endless civil unrest and disasters.

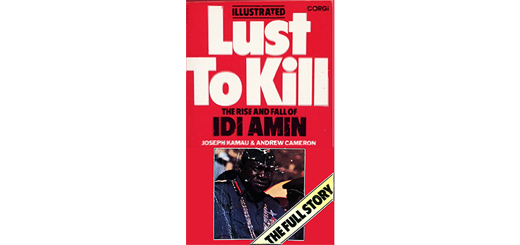

In Uganda, I saw, at close quarters, Tanzanian troops gun down Libyan conscripts as they came out of a banana grove with their hands up. I saw Idi Amin’s prisons thrown open, revealing the corpses of victims most hideously tortured.

Frelimo’s war against the Portuguese, Renamo’s war against Frelimo, our own war and the Matabeleland uprising after independence, Ethiopia’s war against Somalia and conflicts in Liberia and Sudan should have prepared me for Somalia in 1993, the second Somali war I saw, this time against United Nations peacekeepers, the Americans among them.

In the end you tire of seeing the terrible things people do to each other. You wonder if there is really any point in describing the senseless tragedies that unfold before you.

In Mogadishu, my photographer and friend, Hansi Krauss, was one of four journalists killed when an enraged mob turned on us on July 12. I was one of three journalists who survived the mob attack. Hansi fell within a few feet of where I was standing.

Hansi had once told told me he hoped that by bringing images of suffering to world attention he threw light upon darkness and, in some way, lessened the excesses of war.

I’d like to think Hansi was right. But the presence of the press, and particularly stills and TV cameras, can often fan the flames of violence rather than douse them.

After four American GIs were blown to bits in a landmine in Mogadishu, jubilant Somalis danced on lumps of severed flesh for the benefit of the cameras. I saw a human shoulder, still in the charred shreds of a camouflage shirt, being kicked about like a football.

I thought, far from shaming Somalis into behaving with more restraint, our reports of the incident were more likely to provoke their anger and a greater thirst for revenge by the American soldiers in the U.N. coalition.

Conditions in Mogadishu afterwards deteriorated as hundreds more belligerents were killed every week.The spiral of violence was set to cross new boundaries, with every new atrocity being more vicious than the last.

MOGADISHU ON THE GROUND: BLACKHAWK DOWN

Hansi Krauss, who photographed the violence and chaos in Sarajevo with distinction and great bravery – he dragged a wounded colleague out of the arc of fire of snipers there – would have argued that without the withering light of public exposure, things could have been a lot worse.

At least Hansi died with some belief in what he was doing. We had gone to take a closer look a villa the Americans had attacked with helicopter gunships, believing it was a warlord base, killing 54 civilians. The noise and earthshaking force of the missile and machine gun attack attracted angry crowds who got there just as we did.

Hansi, two other photographers and a TV cameraman first jumped out of the cars into their midst. We had been in dangerous crowds before. Hostile gunfire started, the crowd erupted and a hail shots and rocks slammed against our cars.

Hansi went down, bludgeoned with a rock and shot in the chest. Dan Eldon made the perimeter of the villa, started to run into warren of adjacent houses and hovels. He went down too. I couldn’t see what happened to Hos Maina and Anthony Macharia. Our bodyguard yelled for me to get back into the rented Range Rover. He pushed me to the floor of the car and began shooting into the air above my head.

My passenger window shattered and hands were tearing at my shirt. Others were trying to stall the car, lift it on one side to overturn it and kill us too. The driver began speeding away, thumping the car’s bodywork dully into anyone in the way. We got out of “the killing ground” and out of range of the AKs firing at us. The crowds swelled as the Frenchman, the Italian and I got away.

The attackers were firing into the air now, and screaming in triumph over the bodies of our dead.

Later, a stunned silence settled over the hotel where foreign journalists stay. We sat for a long while on the flat roof, staring into our tumblers of whisky, not caring to listen to Mogadishu’s loud nightly concerto of gunfire and explosions or watch the tracer bullets criss-crossing the night sky like fireworks.

For once, these were our dead, not the scores of the nameless, faceless dead of battle and skirmish and disaster we write about every day. Our dead had names and faces. One liked Neil Young, another had an Edith Piaf tape his mother gave him on his last birthday. We had been listening to it the night before he was killed. His body was mutilated by the mob. Some hours later his blood-soaked shoes were dumped outside the front gate of the hotel, a converted office building, as a further warning to us, we were told.

I collected up Hansi’s belongings from his room at the Al Sahafi – his toothbrush was still damp – and there was a novel open on the pillow of his unmade bed. It was Patriot Games by Tom Clancy, just begun and left open at page 14. The cover showed Harrison Ford, who played the CIA man Jack Ryan in the film of the book. I spoke to Hansi’s family on a satellite phone, we arranged for our four dead to be flown by the U.N. to Nairobi where their families would take over the funeral arrangements.

Hansi Kraus was shot after the mob ripped off his flak jacked. Then the killers demanded a ransom for his body.

Our media bodyguards were able to snatch back his body at gunpoint more than 24 hours later. We wrapped him in a sheet from my bed and drove him to the American mortuary where I had to formally identify him, sign the death certificate and hear them read a verse from the Bible. We burnt the sheet, washed the Hansi’s reeking blood out of the back of the car, and I bought a body bag from the Americans. Hansi’s camera was retrieved, his last frames were a blur as he went down snapping the shutter.

Death in war had so suddenly become more to us than a mere paragraph in a newspaper somewhere. When we write of the numbers of those killed in wars or bombings, we forget the families who are in grief every single day the world over; they do for their dead – and much, much more – what I did for Hansi Krauss, aged 30, a man with a name, a face, a personality, kindness, a sense of humour, a man with a fiancé, a man with loved-ones and ambitions and dreams, a man with a life.

When routine casualty and fatality figures are announced, we should try to reflect on this